Note: some links and images present bodily functions including airways and bowels

Once upon a time there were two patients. Each had surgery resulting in a colostomy, an opening (ostomy) in the abdomen where the large intestine (colon) is rerouted and exits the front of the body, not from one’s rear via the anus, but from the “stoma,” the end of the intestine that protrudes through the abdominal wall. A special reusable and disposable bag is attached carefully to this opening to catch the gas and poop, no matter how runny or hard. It can be emptied as needed in the toilet, and has to be replaced every 3-5 days. Odors and leaks happen on occasion.

Both clients were female, white, and about 80 years old. Neither knew ahead of time this was in the cards. Both had a severe intestinal blockage and were given a heads up by the surgeon that a colostomy might be the outcome. One of them, we’ll call her Liz, was rather perturbed with it, and called it unnatural, having what is supposed to be contained inside of the body, on the outside.

Occupational therapists assess the “self-care” realm of activities of daily living. In the case of a new colostomy, evaluation includes considering how the client feels about it, their knowledge about how it works, their visual acuity, fine motor skills, sensation, and cognition. These factors impact one’s success in managing the colostomy independently during toileting, bathing, and dressing, in addition to maintaining the supplies for it and attaching and detaching bags safely and effectively.

Liz was unusual in succinctly expressing her distaste for this “cure.” Many have been wary of it, some have kept a stiff upper lip and moved through the training without much comment. Others previously lacked the cognition to live without assistance, so family or caregivers would be managing this new development, along with other daily needs that had already been managed for the client, e.g. insulin injections, medications, food preparation, and so forth.

Liz had been completely independent in her life prior to surgery. Yet, she had some low vision issues and said she would have nothing to do with managing this new thing. Nursing was taking care of it. She had no available family or friends to assist. I asked her if she would’ve made a different decision about the surgery had she known before what she knew now. She said there was no choice. I mentioned Atul Gawande’s book, Being Mortal, and how in today’s medical arena, it is helpful to have ongoing conversations about what we think we want in our lives; to flesh out what is important for quality of life. Gawande, a surgeon, is very eloquent in his book, as well as in the Frontline special that portrays the story of his father and of a few of his patients.

Liz had been informed that this was one possible outcome, but she hadn’t really taken in what it meant. When I asked her about advanced directives, she said she had none, but that she would not want to be revived in her current condition. Her decisiveness shocked me. When she demanded to know how to get that clarified in writing, I found out who she needed to talk to about “the POLST,” and a meeting with her doc was set up.

Colostomies had not occurred to me as something to consider in an advanced directive discussion. Families talk about life support, breathing machines, paddles, maybe even feeding tubes, but colostomies? Who even knows what that is? It ranked in the amputee category in my unconscious. You still function but adapt. I told Liz, she had raised a good point— that maybe it should be on the list of life supporting measures that might be unwelcomed and thus, discussed in family conversations, depending on the participants’ tolerance for bodily function conversations.

That is part of the problem. Bodily fluids tend to be stigmatized. A brief google search of colostomies on the internet brings up younger persons taking selfies of their bags, posting How-To videos, and beginning to destigmatize the idea. One person’s abnormality is another’s lifesaver.

Rhoda who was quite hard of hearing, had also lived independently before her surgery and had previously overcome financial, emotional, and physical setbacks. She seemed to view this as nothing more than a little bump in the road. She reported that, though her nurses had been performing her colostomy care, she could and would do it without assistance. She was still glowing from pride from having won the fight of her life years before. Giving up her life now for a poopy inconvenience might have struck her as nonsense, had she been able to hear such a perspective.

Another patient, Janet, was completely deaf, had a feeding tube and a tracheostomy—a hole in her neck, but no colostomy. I’ve always thought a feeding tube would be a reason to cut the cord to life. But Janet taught me otherwise. She was clean, brushed her teeth, didn’t smell like liquid food, walked to the bathroom, carried on entertaining conversation via the written word, and obsessively organized her small room. She was a controller, but a pleasure to visit.

I used to think if I ever got cancer, I wouldn’t do chemo. I’d just go off into the sunset. Then I got cancer. And I thought my kids were too young for me to leave yet. So, I did the chemo, and it turned out fine, except I decided I was glad I lived not just for my kids, but for my own love of life too. Janet showed me that if I need a feeding tube, I can still hang with my kids and give them hell. I might even be able to control them!

Make time for those hard conversations. Knowledge is power. “Shit holes” are in the news these days. Let’s use the term literally, in meaningful discussion focused on how we wish to live and die.

SD

start gathering data for a book project—Portland Places by MAX (the Light Rail—Metropolitan Area eXpress). First chapter: Washington Park MAX station. During the Winter Solstice, I’d come across its reputation as the deepest subway station in the world, bar one in Russia. Could it provide enough incentive to push me out of my comfort zone, to navigate alongside the masses? Do I crave depth? Three months had passed. At last, in the spirit of Harriet the Spy , my 4th grade heroine, I had decided to mingle.

start gathering data for a book project—Portland Places by MAX (the Light Rail—Metropolitan Area eXpress). First chapter: Washington Park MAX station. During the Winter Solstice, I’d come across its reputation as the deepest subway station in the world, bar one in Russia. Could it provide enough incentive to push me out of my comfort zone, to navigate alongside the masses? Do I crave depth? Three months had passed. At last, in the spirit of Harriet the Spy , my 4th grade heroine, I had decided to mingle.

Bend National Park in February on a Sierra Club hiking trip. She showed up at mile 7 of a 12-mile round trip South Rim hike. My leg cramped more with each passing mile, and I could hardly walk the next morning, but she led me to a peaceful soak in the natural hot springs alternating with immersion in the cold Rio Grande opposite the hot tub wall.

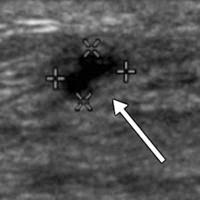

Bend National Park in February on a Sierra Club hiking trip. She showed up at mile 7 of a 12-mile round trip South Rim hike. My leg cramped more with each passing mile, and I could hardly walk the next morning, but she led me to a peaceful soak in the natural hot springs alternating with immersion in the cold Rio Grande opposite the hot tub wall. Five freeze shots, of a snow storm uglier than the one that was happening outside the window. My breast images had a darkness that trumped the gray shrouding of the Willamette. How could they interpret this stuff, I wondered as I tried to make sense of what I saw. It made me sympathize with the conspiracy theorists out there. I laid back down, staring at the ceiling tiles and chastising myself. Boy is Denial a powerful thing. When do we ever learn? My mind was racing and I KNEW She was back. Otherwise, why would the tech have gone to get the doctor to tell me?

Five freeze shots, of a snow storm uglier than the one that was happening outside the window. My breast images had a darkness that trumped the gray shrouding of the Willamette. How could they interpret this stuff, I wondered as I tried to make sense of what I saw. It made me sympathize with the conspiracy theorists out there. I laid back down, staring at the ceiling tiles and chastising myself. Boy is Denial a powerful thing. When do we ever learn? My mind was racing and I KNEW She was back. Otherwise, why would the tech have gone to get the doctor to tell me?